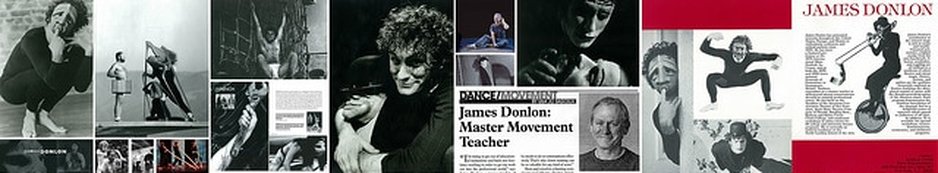

A Conversation with James Donlon (2012)

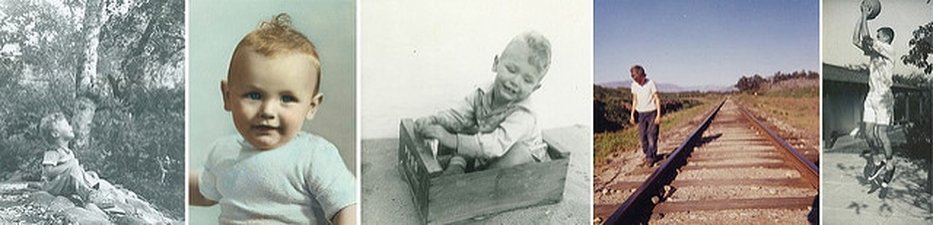

What evidence do you find in your childhood of your propensity for physical theatre? How did you first discover your passion for miming and clowning?

JD: As a boy growing up in a Southern California farming region on the coast, I was exposed to many natural landscapes and outdoor experiences in my daily life. I wandered through expansive fields, amazing mountains, and an ocean horizon full of islands and sky. I catapulted myself with a run, leaping from boulder to boulder down the streambeds, never touching the water. I caught trout with my bare hands. I played basketball alone for hours on the small ranching town playground, learning the limits of the body through time and space.

My mother was a painter who taught me about perspective, texture, and color. An engineer, my inventive father shared his knowledge of how objects kinetically interacted. As a child, I felt the pulse and power of dramatic movement as I manifested the images, characters, and animals I encountered in my books. My passion for mime and clown came years later, when I discovered the profound physical creative play I had always experienced growing up could be shaped and given a stage through acting and theatre. My first acting class at Humboldt State University was the genesis. I was later invited by my professor to perform with him in a town squarefestival as a mime. My career was launched.

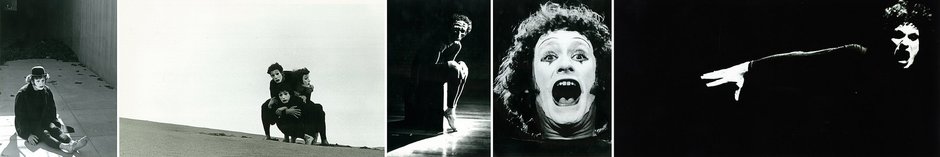

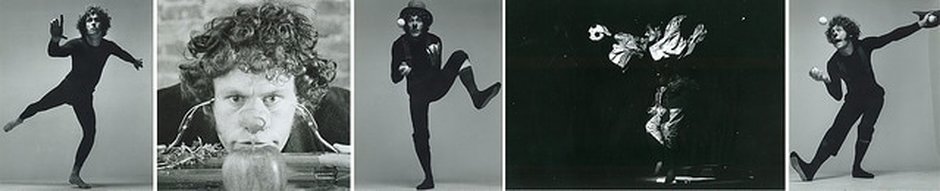

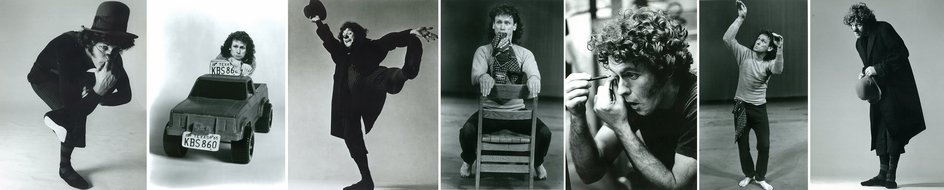

You once described yourself as a “neoclassic clown,” which you say is “a theatre artist who is free to use any means possible to communicate.” What means have you employed to communicate over the course of your career?

JD: My communication skills have been based in dramatic gesture,movement improvisation, masks, circus skills, dance, voice, language, and the power of illusion and fantasy through mime.

After four decades of teaching and performing around the world, you founded the Flying Actor Studio in 2008. You served as a master teacher and director at the San Francisco–based physical theatre school. What was at the heart of your teachings?

JD: Two things: 1) the power of the imagination and 2) the ability to transform an empty space into a profound magical world that celebrates the passion to live and express a point of view.

JD: My communication skills have been based in dramatic gesture,movement improvisation, masks, circus skills, dance, voice, language, and the power of illusion and fantasy through mime.

After four decades of teaching and performing around the world, you founded the Flying Actor Studio in 2008. You served as a master teacher and director at the San Francisco–based physical theatre school. What was at the heart of your teachings?

JD: Two things: 1) the power of the imagination and 2) the ability to transform an empty space into a profound magical world that celebrates the passion to live and express a point of view.

Backstage West contributor, Jackie Apodaca, is a former student of yours. In 2005, she wrote an article titled “What I Learned from My Favorite Teacher,” in which she quoted you as saying, “If you don’t know what to do, stand still.” Tell me about your philosophy of stillness.

JD: The use of stillness is necessary for dramatic action, just like silence is necessary for sounds and words to emerge. How does slamming a door achieve its effect? Is it the sound cutting through the silence, or the silence returning after? One must live in the dark to understand the rays of the sun. A sense of stillness allows circumstances to enter the creative system, freeing one to make choices accordingly. Moving from stillness to action is a new birth. Returning to stillness is preparation for a new beginning.

JD: The use of stillness is necessary for dramatic action, just like silence is necessary for sounds and words to emerge. How does slamming a door achieve its effect? Is it the sound cutting through the silence, or the silence returning after? One must live in the dark to understand the rays of the sun. A sense of stillness allows circumstances to enter the creative system, freeing one to make choices accordingly. Moving from stillness to action is a new birth. Returning to stillness is preparation for a new beginning.

Carl Jung once said, “The dynamic principle of fantasy is play, which belongs also to the child, and as such it appears to be inconsistent with the principle of serious work. But without this playing with fantasy no creative work has ever yet come to birth.” Do you find that most adults have difficulty remembering how to play? How do you help them rediscover the world of make-believe?

JD: The child sees and feels everything with honesty and reaction. The adult learns to discard behavior that interferes with the economy of achieving the work-related goal. The child has no agenda other than to experience through innocence. The adult keeps focused on the work, forgetting other movement behaviors, colors, and emotions. It’s not that adults don’t remember how to play. They are just … out of shape. Our work rewards us. The adult ability to be rewarded by the wonders of time and space, the tools of the artist, is rusty. The physical “junk” of contemporary life shapes us. We have lost our courage and skill to make something out of nothing. Very often adults feel prior entitlement to things so easily accessible in the modern world. Play is the courageous, liberating dialogue between the mind/body and the surrounding world. My advice is: stop, collect yourself, see the world, have a point of view, enter that world, and let it push you, as you push it. It’s fun.

JD: The child sees and feels everything with honesty and reaction. The adult learns to discard behavior that interferes with the economy of achieving the work-related goal. The child has no agenda other than to experience through innocence. The adult keeps focused on the work, forgetting other movement behaviors, colors, and emotions. It’s not that adults don’t remember how to play. They are just … out of shape. Our work rewards us. The adult ability to be rewarded by the wonders of time and space, the tools of the artist, is rusty. The physical “junk” of contemporary life shapes us. We have lost our courage and skill to make something out of nothing. Very often adults feel prior entitlement to things so easily accessible in the modern world. Play is the courageous, liberating dialogue between the mind/body and the surrounding world. My advice is: stop, collect yourself, see the world, have a point of view, enter that world, and let it push you, as you push it. It’s fun.

There is a growing interest in somatic psychotherapy methods such as Hakomi and expressive therapy. Movement therapy emphasizes a deeper connection between the mind and body than Cartesian dualism would have us believe exists. Have you witnessed the therapeutic effects of physical movement when working with people who may be suffering from grief, depression, PTSD, or other psychological traumas?

JD: Yes. Take one movement as prescribed and go to bed. Sleep well. Dream.

I love what you said in a Backstage East article, “Movement transcends linguistic borders. Even though I do use language in my work, I like to think of it as a gesture, and I think of movement as a voice.” Can you elaborate on that statement?

JD: Anything conducive to a good vocal conversation or dialogue—clarity, economy, energy, vocabulary, diction, volume, focus, musicality, point of view—is also possible with movement. Movement on all levels is a conversation with space and time.

JD: Yes. Take one movement as prescribed and go to bed. Sleep well. Dream.

I love what you said in a Backstage East article, “Movement transcends linguistic borders. Even though I do use language in my work, I like to think of it as a gesture, and I think of movement as a voice.” Can you elaborate on that statement?

JD: Anything conducive to a good vocal conversation or dialogue—clarity, economy, energy, vocabulary, diction, volume, focus, musicality, point of view—is also possible with movement. Movement on all levels is a conversation with space and time.

In that article, you also cited Steven Linsner’s quote, “A clown is a poet who is also an orangutan.” What does that mean to you?

JD: The clown is the spokesperson, caretaker, judge, and interpreter of a culture. The culture is defined by the natural world it springs from, and a relationship with that natural world must be established to coexist. The clown is free to comment on the behavior, traditions, and history of the culture. The clown works with truth and image. The clown is a force of nature like the orangutan. People find joy and pathos in the discovery and recognition of the truth in their culture. Clowns are shamans. They derive their power and incite from nature, like the orangutan. The clown uses natural instinct with an acrobatic mind and body.

Are you familiar with New Zealand comic Sam Wills, known as The Boy With Tape on His Face? He is a master of audience participation, and he communicates entirely through his movements and facial expressions. He used to do more traditional stand-up, but it was when he stopped talking that his performances became riveting. I suspect the silence forces a degree of attention not required by spoken language performances. The audience must exercise their imagination to fill in the gaps.

JD: Movement is never really silent. The music of the supporting breath and the activity of the muscles produces textures that resonate in space. Dance-mime-gesture and music are extensions of each other. Movement is what children are about. But their behavior is accompanied by many sounds, vocal and otherwise. When audiences see movement on stage, they sense the beginning of life and are happy. The vivid sense memory of their childhood imagination returns.

Shakespeare understood the value of the Fool, a trope that has played a crucial role in drama for millennia. Why do you think the jester is such a timeless archetype? What can the clown teach us today?

JD: The true clown is an actor. Noted jester and actor Geoff Hoyle says, “I’m not always clowning when I’m acting, but when I’m clowning I’m always acting.” The clown holds the mirror to our faces. We learn to see ourselves as we were, are, and could be.

JD: The clown is the spokesperson, caretaker, judge, and interpreter of a culture. The culture is defined by the natural world it springs from, and a relationship with that natural world must be established to coexist. The clown is free to comment on the behavior, traditions, and history of the culture. The clown works with truth and image. The clown is a force of nature like the orangutan. People find joy and pathos in the discovery and recognition of the truth in their culture. Clowns are shamans. They derive their power and incite from nature, like the orangutan. The clown uses natural instinct with an acrobatic mind and body.

Are you familiar with New Zealand comic Sam Wills, known as The Boy With Tape on His Face? He is a master of audience participation, and he communicates entirely through his movements and facial expressions. He used to do more traditional stand-up, but it was when he stopped talking that his performances became riveting. I suspect the silence forces a degree of attention not required by spoken language performances. The audience must exercise their imagination to fill in the gaps.

JD: Movement is never really silent. The music of the supporting breath and the activity of the muscles produces textures that resonate in space. Dance-mime-gesture and music are extensions of each other. Movement is what children are about. But their behavior is accompanied by many sounds, vocal and otherwise. When audiences see movement on stage, they sense the beginning of life and are happy. The vivid sense memory of their childhood imagination returns.

Shakespeare understood the value of the Fool, a trope that has played a crucial role in drama for millennia. Why do you think the jester is such a timeless archetype? What can the clown teach us today?

JD: The true clown is an actor. Noted jester and actor Geoff Hoyle says, “I’m not always clowning when I’m acting, but when I’m clowning I’m always acting.” The clown holds the mirror to our faces. We learn to see ourselves as we were, are, and could be.

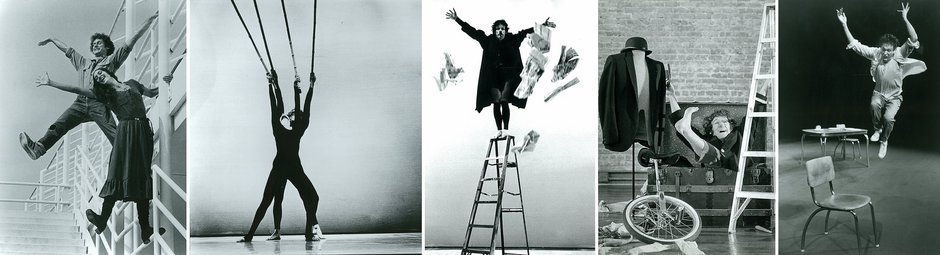

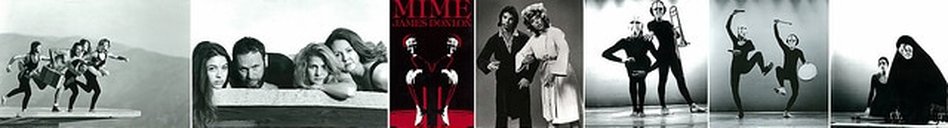

You are the only physical theatre artist who has ever been invited to create and perform with legendary street mime Robert Shields of Shields and Yarnell fame. Tell me about that experience.

JD: I first knew Robert Shields as a brilliant San Francisco street mime in 1974. He was the soul of the city, captivating Union Square. I had a mime school two blocks away, the gateway for my international tours. Robert walked in on my rehearsal one day, extended his hand and said, “Hi, I’m Robert Shields.”

From that time on, we found ourselves performing in the same mime festivals, and sometimes we improvised together in a festival studio. The merging of our different technical styles amazed students. We would soon go our separate paths: Robert into show business and television, and I into theatre and actor training. Many decades later, I produced an international physical theatre festival in Santa Barbara, California. I invited Robert to perform. We attended each other’s one-man show and enthusiastically decided to find a future time to work together.

A year later, Robert invited me to do a show with him in Sedona, Arizona, where he lived. It was to be a kind of Shields & Donlon “Greatest Hits.” It was a tremendous experience. We meshed perfectly. During the show, I introduced Robert’s famous robot character from a historical perspective. I had been in San Francisco 30 years earlier when he had polished his craft. Besides our “classics,” we created a new piece with my masks. We were like old gladiators as we warmed up. We received a standing ovation from the sold-out 2,000-seat hall. We held a true respect for our personal arts. Robert said to me, “You’re from theatre, and I’m from show business.” But we needed each other. The audience loved it.

JD: I first knew Robert Shields as a brilliant San Francisco street mime in 1974. He was the soul of the city, captivating Union Square. I had a mime school two blocks away, the gateway for my international tours. Robert walked in on my rehearsal one day, extended his hand and said, “Hi, I’m Robert Shields.”

From that time on, we found ourselves performing in the same mime festivals, and sometimes we improvised together in a festival studio. The merging of our different technical styles amazed students. We would soon go our separate paths: Robert into show business and television, and I into theatre and actor training. Many decades later, I produced an international physical theatre festival in Santa Barbara, California. I invited Robert to perform. We attended each other’s one-man show and enthusiastically decided to find a future time to work together.

A year later, Robert invited me to do a show with him in Sedona, Arizona, where he lived. It was to be a kind of Shields & Donlon “Greatest Hits.” It was a tremendous experience. We meshed perfectly. During the show, I introduced Robert’s famous robot character from a historical perspective. I had been in San Francisco 30 years earlier when he had polished his craft. Besides our “classics,” we created a new piece with my masks. We were like old gladiators as we warmed up. We received a standing ovation from the sold-out 2,000-seat hall. We held a true respect for our personal arts. Robert said to me, “You’re from theatre, and I’m from show business.” But we needed each other. The audience loved it.

What was it like teaching movement to Kathy Bates, Francis McDormand, Mary Kay Place, and Benjamin Bratt? How does movement for film and television differ from movement for stage?

JD: Successful actors who work on the highest, most prestigious levels have committed their mind and body to elevate their craft. They work hard, and their prowess is not an illusion. My teaching and coaching experience with these actors has been wonderful. They are open and ready.

Kathy Bates explained to me that the best film actors have been trained in the theatre. Their physical skills are very accomplished. Film is the art of action and behavior, more so than language. It is a visual art. Film requires a sophisticated understanding of movement, sharing the same foundation as theatre. The circumstances inherent in each require different creative choices in terms of size and focus. But the goals are the same: to be economical and know where your audience is. Oscar winner Javier Bardem worked with me like a skillful athlete. I discovered that he could be a very good clown, owning wonderful senses of the physical absurd and playfulness. In fact, another of the leading film actors I coached, Academy Award nominee David Strathairn, was a clown student in Ringling Bros. Circus before his film career.

JD: Successful actors who work on the highest, most prestigious levels have committed their mind and body to elevate their craft. They work hard, and their prowess is not an illusion. My teaching and coaching experience with these actors has been wonderful. They are open and ready.

Kathy Bates explained to me that the best film actors have been trained in the theatre. Their physical skills are very accomplished. Film is the art of action and behavior, more so than language. It is a visual art. Film requires a sophisticated understanding of movement, sharing the same foundation as theatre. The circumstances inherent in each require different creative choices in terms of size and focus. But the goals are the same: to be economical and know where your audience is. Oscar winner Javier Bardem worked with me like a skillful athlete. I discovered that he could be a very good clown, owning wonderful senses of the physical absurd and playfulness. In fact, another of the leading film actors I coached, Academy Award nominee David Strathairn, was a clown student in Ringling Bros. Circus before his film career.

You are one of the world’s most respected master teachers in physical theatre. Who were your mentors, your lights?

JD: My first mime partner Robert Francesconi. My first acting teacher Phillip Mann. The clown Dimitri. All the students I have taught. I believe a teacher is only as good as his students. Every time I step into a studio, I learn something from my students.

What are you most excited about with regards to the new Flying Actor Studio in Ashland?

JD: I want to provide an atmosphere of creative collaboration involving hard-working students with restless imaginations in a studio surrounded by an amazing natural environment. All of these elements contribute to strengthening those revelations I experienced long ago in that small California farm town. I want to share my knowledge with my students, colleagues, and the Ashland community because I know this “dialogue” will spark life to be lived to the fullest.

JD: My first mime partner Robert Francesconi. My first acting teacher Phillip Mann. The clown Dimitri. All the students I have taught. I believe a teacher is only as good as his students. Every time I step into a studio, I learn something from my students.

What are you most excited about with regards to the new Flying Actor Studio in Ashland?

JD: I want to provide an atmosphere of creative collaboration involving hard-working students with restless imaginations in a studio surrounded by an amazing natural environment. All of these elements contribute to strengthening those revelations I experienced long ago in that small California farm town. I want to share my knowledge with my students, colleagues, and the Ashland community because I know this “dialogue” will spark life to be lived to the fullest.